Miami Show Explores the Evolution of Judy Chicago

by: Farrah Nayeri

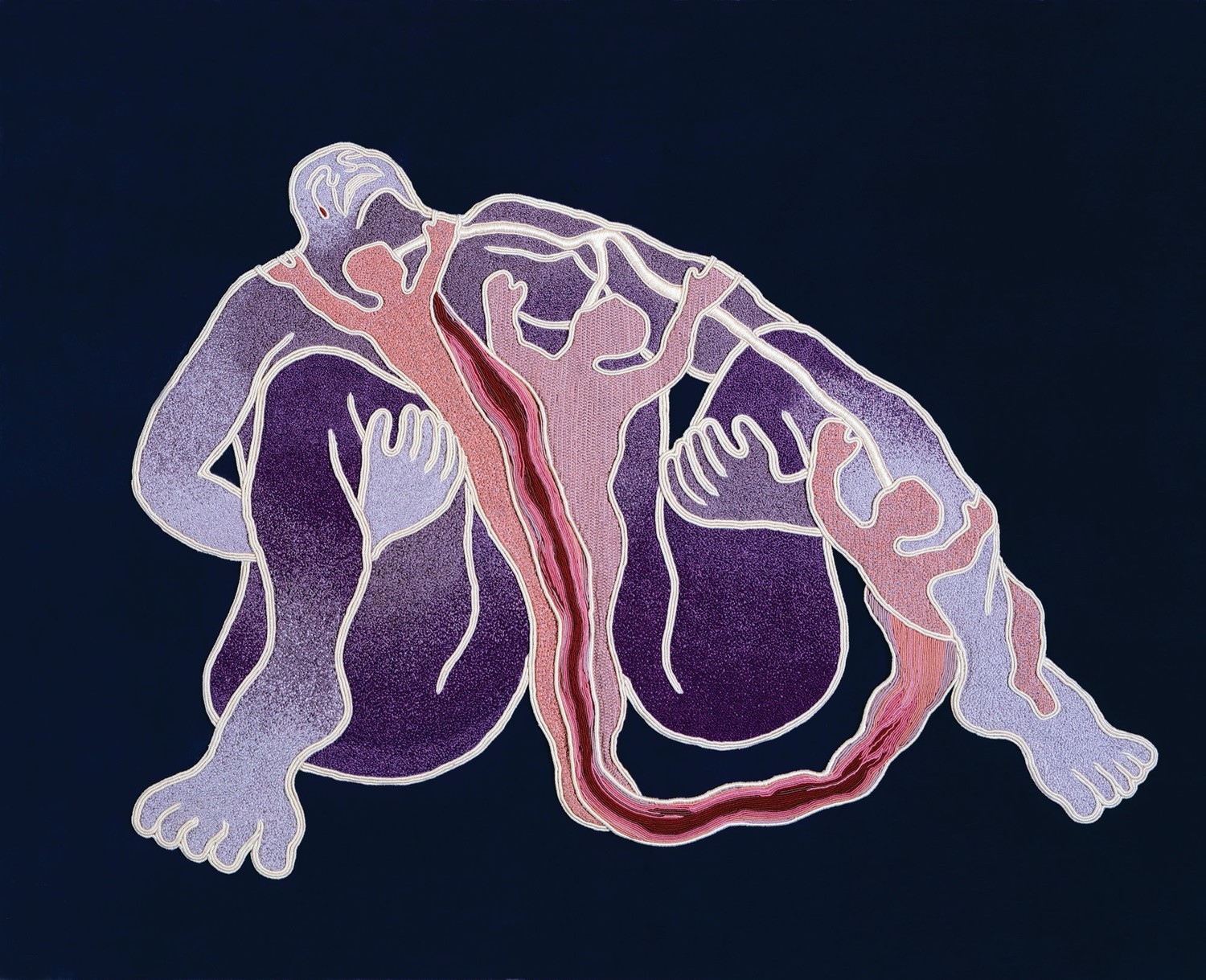

In the early 1980s, the American artist Judy Chicago teamed with more than 150 needleworkers to depict a subject matter that could not be more universal: childbirth. Through embroideries, textiles and one large-scale drawing, her “Birth Project” (1980-85) came to represent the process by which human beings entered the world.

“I actually witnessed a birth as one of the first things I did: I educated myself, because there was so little art on the subject, at least that was visible at that time,” Ms. Chicago said in a recent interview. “To see the vulva giving birth is to see an absolutely essential challenge to the idea of female passivity. So I was focused on something that I’ve even focused on throughout my career: Can the female experience be a pathway to the universal in the way male experience has been?”

“The Birth Project” now takes pride of place in an exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, that has opened at about the same time as Art Basel Miami Beach. “Judy Chicago: A Reckoning” is a survey of the first 30 years of the career of a woman who, like so many female artists of her generation and those before, was long shunned by her peers and who is receiving recognition late in life.

The exhibition starts in the 1960s and focuses on the period when Ms. Chicago moved from abstraction to figuration and developed a visual language of her own. It includes about 36 works as well as an ensemble of about 140 drawings, which ICA Miami’s artistic director, Alex Gartenfeld, discovered in crates when he visited the artist in her studio in Belen, N.M., in 2014 (and got the idea for the show).

Ms. Chicago is best known for “The Dinner Party” (1974-1979), a permanent installation at the Brooklyn Museum that consists of a triangular banquet table with 39 place settings honoring an important female figure in history. Each place setting has at its center a plate with a raised vulva- or butterfly-shape motif. Honorees include the author Virginia Woolf, the poet Sappho and the artists Georgia O’Keeffe and Anna Maria van Schurman. As Ms. Chicago said in the interview, “There are all these women at the table who were from different cultures, religions, ethnicities, centuries, professions, and the only thing they all had in common was they all had vaginas, which links to the fact that they were mostly erased from history.”

That erasure, which Ms. Chicago long suffered from because of her bold depiction of it, is a central theme of her art, and of the exhibition.

“Judy has always wished to contend with the way that art history has written women out,” said Mr. Gartenfeld, the show’s main curator. “Her work is about the cannon and the history of women, so I would say it’s fitting for art history to ensure that Judy is an important part of it.”

“The work looks incredibly fresh formally,” he added. “Judy has a hand and a sense of color that speaks not just to the time that she made it, but today.”

Ms. Chicago was born Judy Cohen in Chicago in 1939 and started studying art when she was 5. She then enrolled at the University of California in Los Angeles. While at U.C.L.A., she took a year off and went to New York.

“It was the heyday of abstract expressionism,” she recalled in the interview. “That interested me, and it coincided with a collision with figurative art. I began going back and forth from abstraction to figuration.”

Ms. Chicago returned to Los Angeles and became part of the local art scene, which, as she said, “was not exactly receptive to my imagery.” So she became more minimal, as the early sculptures in the exhibition demonstrate.

After about a decade of that, “I decided I was trying to fit into an aesthetic that was not really comfortable to me,” she explained. “That’s when I made this radical change. I tried to figure out how to fuse my gender and my interest in issues around women’s experiences with the abstract form language that I had built during my first decade of practice.”

“The Birth Project” is a crucial phase in that artistic process. Immediately after completing “The Dinner Party,” Ms. Chicago looked for illustrations of childbirth and came up short.

As the co-curator Stephanie Seidel explains in the catalog for the ICA Miami exhibition, “Childbirth is a foundational process, yet it is typically kept hidden, suppressed or only hinted at rather than overtly portrayed.” Ms. Seidel recalls being “shocked to discover that there were almost no images of birth in Western art, at least not from a female point of view.”

That is because, according to Ms. Chicago, “male-centered art” has long been associated with the universal. “I’ll never forget standing in the Vatican and looking at a male God reach out his finger and create Man,” she said in an interview published in the catalog. “Birth, which is an essentially female act, had been completely taken over by patriarchal religion.”

“The Birth Project,” which consists of 85 needlepoint and textile works and one large-scale drawing, fills that art-historical gap and is one of a half-dozen sections in the exhibition. The show begins with early minimalist works, then early feminist works, before leading into “The Birth Project” and a section of test plates produced for “The Dinner Party.” It ends with the ensemble of drawings titled “Autobiography of a Year.”

Why did ICA Miami decide to put on a Judy Chicago show now? Because of “the poverty of recognition for important female artists, specifically those working in what could be called a feminist vein,” Mr. Gartenfeld replied. “This is a time of, for better or for worse — mostly for better — increased interest and enthusiasm for, and understanding for, artists who have been working on the challenges of being a woman artist and a woman in art history.”

“Art history is belatedly and begrudgingly coming around to acknowledging female practitioners,” he added. “Judy is a leader in that regard.”

Image: “Birth Tear/Tear,” 1984, macramé over drawing on fabric, which is part of Judy Chicago’s “Birth Project, is being shown at the exhibition “Judy Chicago: A Reckoning” at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami. It runs through April 21.